Friction is known as one of the most longstandig problem in physics, dating back to the times of Leonardo da Vinci in the 1500s. Many great minds have since studied friction, including Coulomb, Euler and Reynolds. However, the underlying mechanisms of frictions remains unknown. I’m obviously not as intelligent as these masterminds, so what makes me believe that I can find something new in this field? The answer is that we got new methods in the form of computers. Powerful computers.

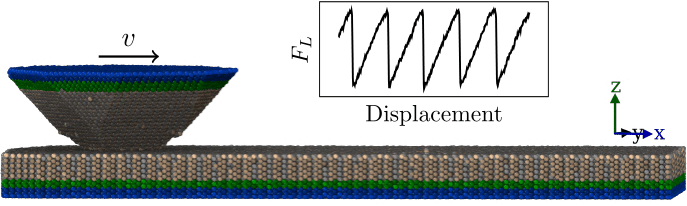

Sliding friction. Illustration shows a single contact sliding on a substrate. The inset presents a typical stick-slip force curve.

Friction is difficult to study because of complex interfacial processes, such as deformation, atomic diffusion and chemical reactions. When performing real experiments, the spatial resolution is typically limited by the optics of microscops and the temporal resolution is restricted by the frequencies spectropic cameras can deliver. In computer simulations, the spatial resolution is only limited by the floating point precision and temporal resolution is limited by the time step specified. As a result, computer simulations are superior to real experiments in spatial and temporal resolution, making it possible to see details that are not possible in real experiments.

Static and dynamic friction is just the same!

In high school physics, friction is usually described as a highly material dependent property, else only dependent on the normal force, following the Amontons–Coulomb law:

\[F_R=\mu N,\]where \(F_R\) is the frictional force, \(\mu\) is the friction coefficient and \(N\) is the normal force. This is in the best case a simplification, as friction is a highly rich quantity.

Additionally, the students learn about static and dynamics friction as two independent phenomena, whereas static friction is the resistance force when two surfaces are stationary and dynamic friction is the resistance force of two substrates of relative motion. However, as no substrate is totally rigid, the substrates will deform when they are in contact and have a relative motion, making the interface in contact for a short time period. Consequently, dynamic friction is actually static, but with a very short contact time! So why do we observe a difference in the measured friction in the static and dynamic case then? The only logical explanation is that the contact time plays an important role.

Frictional aging. The contact area increases with contact time.

Time dependent friction

To investigate our hypothesis from above, we may perform experiments where we measure the static friction force at different contact times. In fact, these kinds of experiments have been performed since the 1950’s (Rabinowicz, 1951). They show the same behavior across a long range of materials: the longer an interface is in contact, the stronger friction. When you think about it, it is not very surprising. Imagine that you face some fresh, smoking hot asphalt. If you walk on the asphalt, you will probably not have a problem, but once you stop, your shoes will stick to the asphalt and if you wait long enough you may get stuck. You can think of it like the shoes gradually “grows” into the asphalt. Even though this is a quite extreme example, it is reminiscent to the process that happens in every friction process. Despite many suggestions, the underlying mechanisms of this time dependent behavior remains elusive.

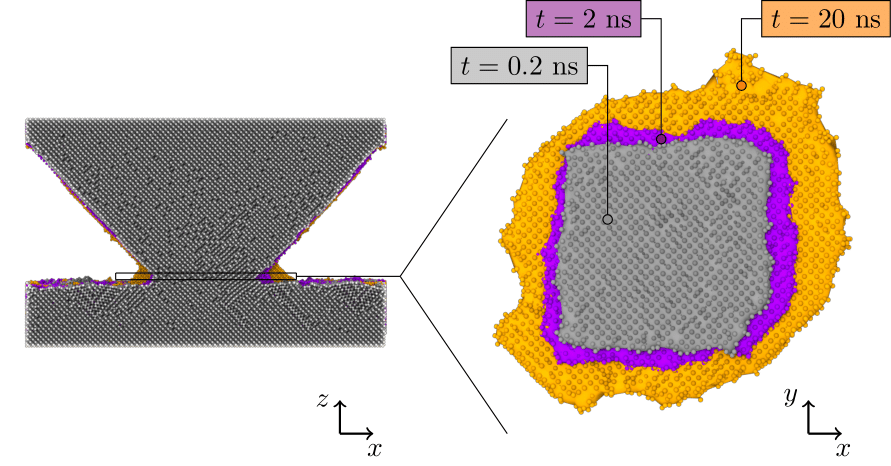

Contact evolution. Note that the real contact area increases with time step, which is the real contact area.

To gain new insights into time dependent friction, I have performed simulations of a single contact point as two surfaces get into contact. What we observed was that surface atoms tend to gather around the contact, increasing the actual contact area between the surfaces and making the interface stronger. This is possible because of surface diffusion and the fact that atoms are strongly bounded around the contact. I refer to (Nordhagen et al., 2023) for more details.

Sliding friction

Most people think about sliding when friction is mentioned. We have already discused the connection between static and dynamic friction, and the theory above has some important implications on the behavior of sliding friction. At low relative velocities between surfaces, the surfaces will stick for a period, then slip and then stick again, conveniently called stick-slip friction. During the stick phase, the two surfaces are attached like they where stationary*, but with a contact time that decreases with increasing relative velocity (the contact time is inversely proportional to the velocity). Since friction increases with increasing contact times, friction will hence decrease with increasing velocity. This dependency has been known since the 1940’s (Dokos, 1946), but was not explained until later.

*This is a logical assumption, but according to some recent works the interface may evolve differently under shear stress than normal stress, even though the interfaces initially are identical (Kilgore et al., 2012; Kilgore et al., 2017)

The onset of asperity sliding.

Friction-velocity relationship

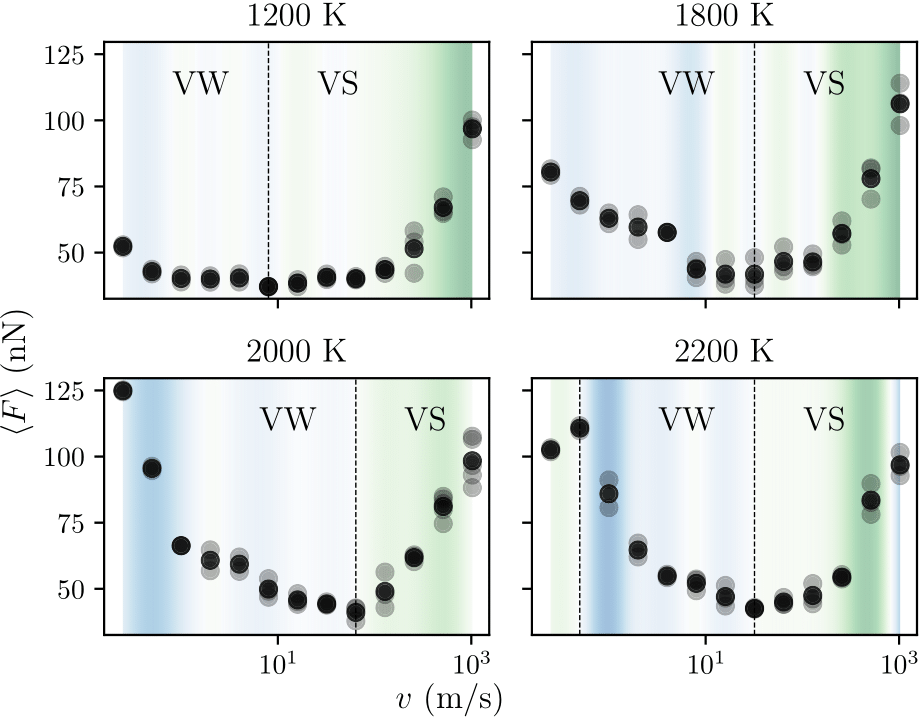

I have performed simulations to investigate the friction-velocity relationship, where the approach is to slide a single contact at various velocities and temperatures. We observe that the friction-velocity curves feature multiple regimes, some where friction increases with velocity and some where friction decreases with velocity (missing reference).

A decreasing friction with increasing sliding velocities at low velocities and increasing friction with increasing velocity at high velocities has been observed in many materials, and has even been suggested as a universal property across all materials (Bar-Sinai et al., 2014).

Friction vs. velocity. Friction decreases at low velocities and increases at high velocities, with a local minimum.

Wear-velocity relationship

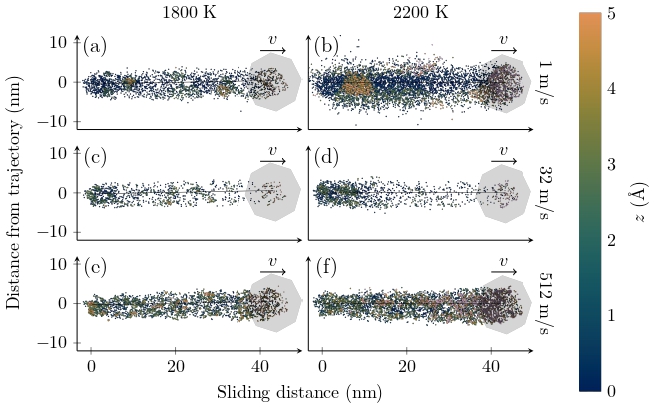

Similar to friction, also wear displays multiple velocity regimes. At low velocities, wear decreases with increasing velocity. At high velocities, wear increases with increasing velocity. This gives a local minimum in wear, similar to friction. The fact that wear is minimal at certain velocities has many important implications, with many industrial applications.

Wear for three different sliding velocities and two different temperatures. Note that wear is minimized at the intermediate velocity for both temperatures.

Even though friction and wear have similar characteristics with velocity, they are not linear - in fact it turns out that wear increases exponentially with friction. The mechanism behind thid has previously been suggested by Jacobs and Carpick (Jacobs & Carpick, 2013).

References

- Rabinowicz, E. (1951). The Nature of the Static and Kinetic Coefficients of Friction. Journal of Applied Physics, 22(11), 1373–1379. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1699869

- Bar-Sinai, Y., Spatschek, R., Brener, E. A., & Bouchbinder, E. (2014). On the velocity-strengthening behavior of dry friction. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 119(3), 1738–1748. https://doi.org/10.1002/2013JB010586

- Dokos, S. J. (1946). Sliding Friction Under Extreme Pressures—1. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 13(2), A148–A156. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4009539

- Jacobs, T. D. B., & Carpick, R. W. (2013). Nanoscale wear as a stress-assisted chemical reaction. Nature Nanotechnology, 8(2), 108–112. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2012.255

- Kilgore, B., Lozos, J., Beeler, N., & Oglesby, D. (2012). Laboratory Observations of Fault Strength in Response to Changes in Normal Stress. Journal of Applied Mechanics, 79(3). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4005883

- Kilgore, B., Beeler, N. M., Lozos, J., & Oglesby, D. (2017). Rock friction under variable normal stress. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth, 122(9), 7042–7075. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014049

- Nordhagen, E. M., Sveinsson, H. A., & Malthe-Sørenssen, A. (2023). Diffusion-Driven Frictional Aging in Silicon Carbide. Tribology Letters, 71(3), 95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11249-023-01762-z