Last week, I attended the Workshop on Large-Scale Deep Learning for the Earth System in Bonn, Germany, and it was a great experience. Given that the workshop specialized in machine learning models for predicting weather and climate, it could hardly be more relevant for my current position at MET Norway. The event featured presentations on cutting-edge deep learning models for weather and climate forecasting.

The workshop was held at the University Club in Bonn. Notably, Bonn is the birthplace of Ludwig van Beethoven, which explains the numerous Beethoven portraits adorning the walls. Image is taken from https://www.axona-aichi.com/projects/archives/58.

Workshop Overview

The workshop spanned two days, with the first day dedicated to weather-related discussions and the second day focused on climate topics. While there were poster sessions and opportunities for discussion between talks, the primary emphasis was on the presentations. A total of 32 talks were delivered to an audience of 120 attendees, alongside 25 poster presentations. The schedule was densely packed, making it challenging to absorb and retain all the information.

Outcomes

Given my primary research interests and the workshop’s intensive schedule, I will focus this post on the weather-related presentations from Day 1 that particularly captivated me. Despite the wide range of topics covered, certain themes were more prominent than others. Here are the hottest topics:

- Transitioning from deterministic to probabilistic models (ensemble models)

- Integration of direct observations with end-to-end machine learning pipelines

- Prediction of extreme weather events

Beyond the scientific insights gained from the workshop, the experience also offered valuable networking opportunities. It was enlightening to meet new colleagues and connect with individuals I had previously only interacted with online. The exchange of ideas and the inspiration derived from these interactions were equally rewarding.

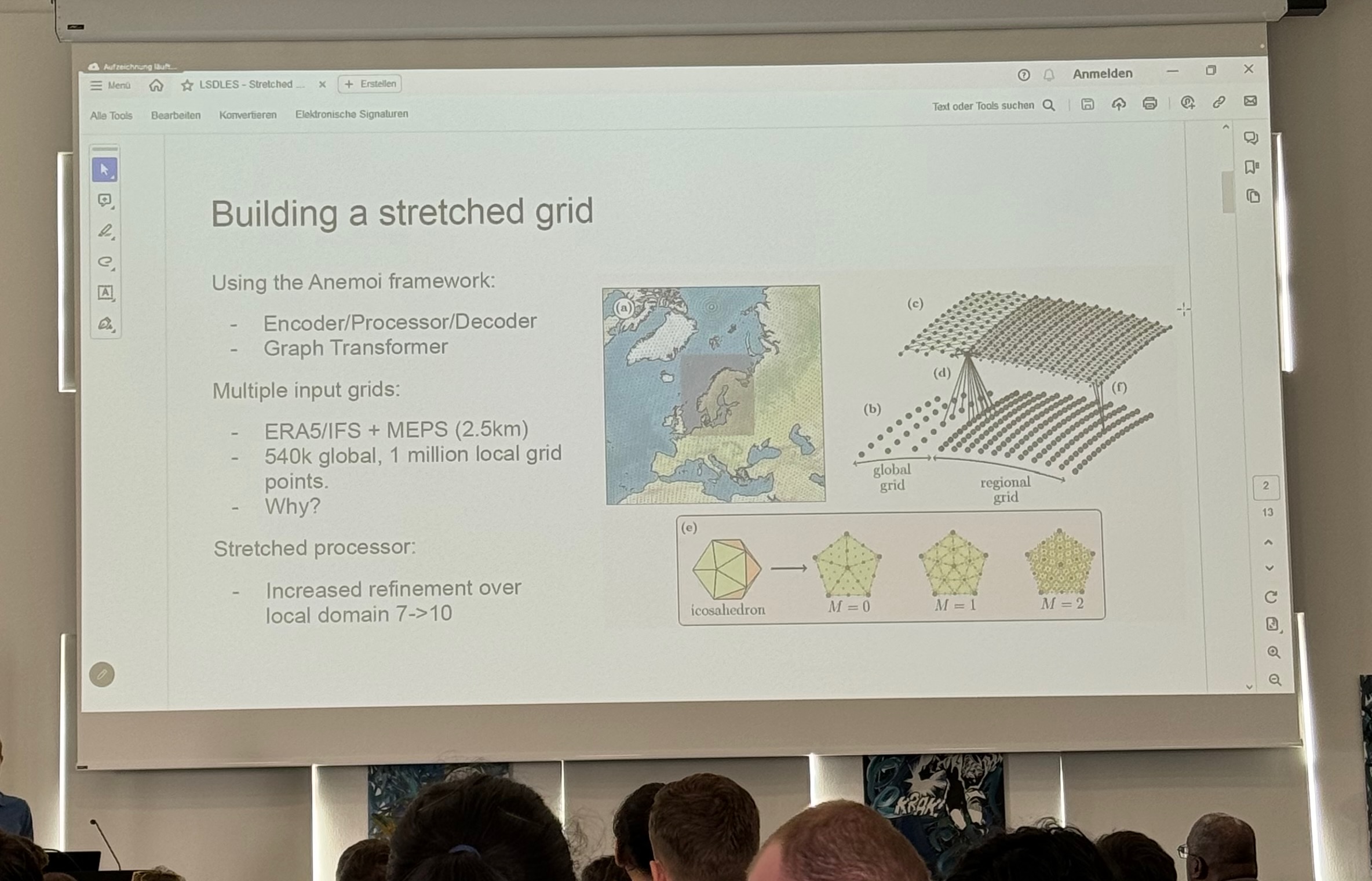

From stretched-grid presentation.

Regional Models

While regional models were not the focus of most presentations at the workshop, I will discuss them first as they align closely with my current work. The second talk of the workshop, presented by Magnus, introduced our global stretched-grid graph neural network (GNN) for regional weather prediction. We have recently released a preprint of our work (arXiv:2409.02891), and I’m eager to share a detailed post about it soon.

Limited Area Modeling (LAM) is a well-established method for regional weather forecasting, wherein the boundaries of the limited area are updated through a separate global model. Joel Oskarsson et al. explored this technique combined with machine learning models to predict the weather over the Nordic regions (arXiv:2309.17370). This approach has now been extended to a probabilistic model based on hierarchical GNNs, which Oskarsson presented at the workshop. In this method, an ensemble of members is generated through a rapid one-step process, providing uncertainty estimates and a skillful distribution of ensemble members (arXiv:2406.04759). Although promising, their performance evaluation was limited to a 10 km spatial resolution.

Another notable presentation was FengWu-GHR, a regional forecast system for China. Their approach significantly differs as they develop a global weather model with a high resolution of 0.09° (10 km) (arXiv:2402.00059). However, this method has several drawbacks. Firstly, the high-resolution model does not align with standard criteria for operational regional forecasts, which typically prefer a resolution of 1-3 km. Secondly, training such a model is resource-intensive, especially if the primary interest is regional weather phenomena. Their model comprises 4 billion learnable parameters, which is 16 times the number of parameters we employ, despite our regional resolution being four times higher.

From Deterministic to Probabilistic Models

Probabilistic models, particularly those relying on ensembles, have become a focal point in the field of machine learning for weather prediction, and for good reason. First, these models are capable of estimating the uncertainty of a forecast, a feature that current conventional operational models utilize by incorporating ensembles. Machine learning models trained with a mean-squared error loss often suffer from the double-penalty problem. This issue arises when a model predicts an event slightly off from its actual position in space and time, resulting in two penalties: one for predicting the event at the wrong location or time, and another for not predicting it at the correct location or time. Consequently, such models tend to smooth the fields rather than predicting sharp events, such as extreme wind and precipitation occurrences.

Ensemble models, however, are evaluated using probabilistic metrics like the Continuous Ranked Probability Score (CRPS). This approach mitigates the double-penalty problem and allows for sharper predictions. The first presentation of the workshop, given by Simon Lang, discussed the integration of ensembles in the Artificial Intelligence Forecasting System (AIFS) code (arXiv:2406.01465). He highlighted two methods for creating ensembles: optimizing probabilistic scores with CRPS loss and generating fields using a generative diffusion model. Lang demonstrated that the ensemble approach eliminates the smoothing problem and yields better results than leading conventional ensemble models.

Martin Andrae presented an innovative concept where diffusion models are conditioned on lead time, enabling them to generate sequential forecasts in parallel (martinandrae.github.io/Continuous-Ensemble-Forecasting). Although the idea is promising, I have reservations about the complexity and practicality of training such a model.

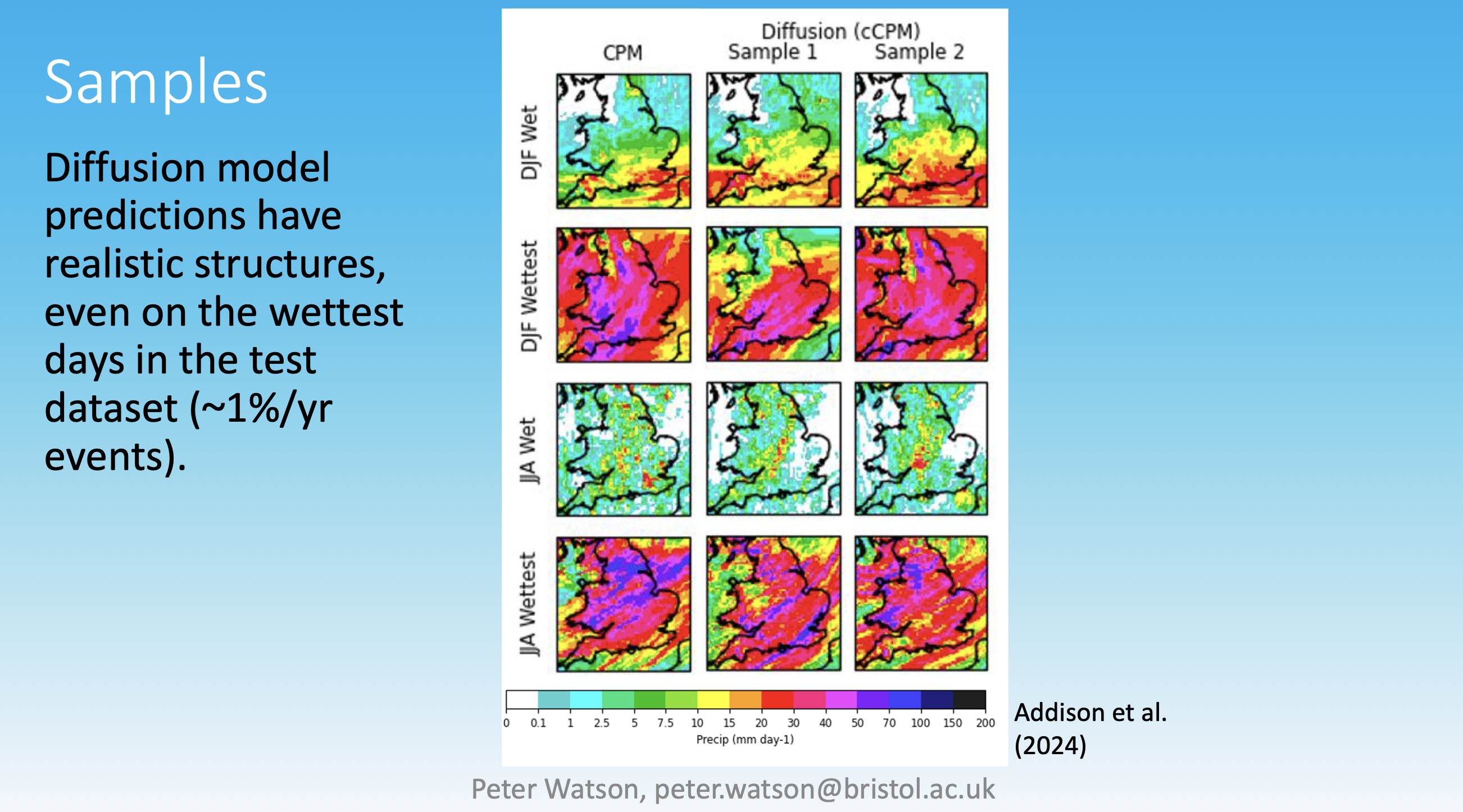

Machine learning diffusion models can predict extreme precipitation. The column on the left shows results from a convection-permitting model (CPM), while the last two columns display two samples generated by the diffusion model. The upper two rows depict extreme precipitation events during winter (December to February, DJF), and the lower two rows are for summer (June to August, JJA). “Wet” indicates a chosen rainy day, and “wettest” represents the wettest day in the test dataset. This slide is from Peter Watson’s talk (arXiv:2407.14158).

Extreme Weather Prediction

Forecasting extreme weather events is among the most critical responsibilities of meteorological institutes worldwide. To achieve accurate predictions, ensemble models must be developed as discussed earlier. Several presentations at the workshop addressed this topic, including Peter Watson’s “Extreme Precipitation,” which introduced and evaluated a probabilistic diffusion model for predicting extreme precipitation events (arXiv:2407.14158). The model successfully predicted extreme precipitation, including the rainiest day in the test dataset (refer to the figure above).

A poster by Leonardo Olivetti compared deterministic machine learning models for extreme weather prediction (see poster here). These models were found to perform poorly on extreme events at long lead times, particularly for extreme wind speeds, mainly due to smoothing. Olivetti also mentioned that machine learning models struggle with wind predictions due to the u-v decomposition, although we observed no improvement when switching to polar coordinates for wind variables. The workshop concluded with a commitment to making extreme weather forecasting a more central topic in next year’s event.

Direct Use of Observations

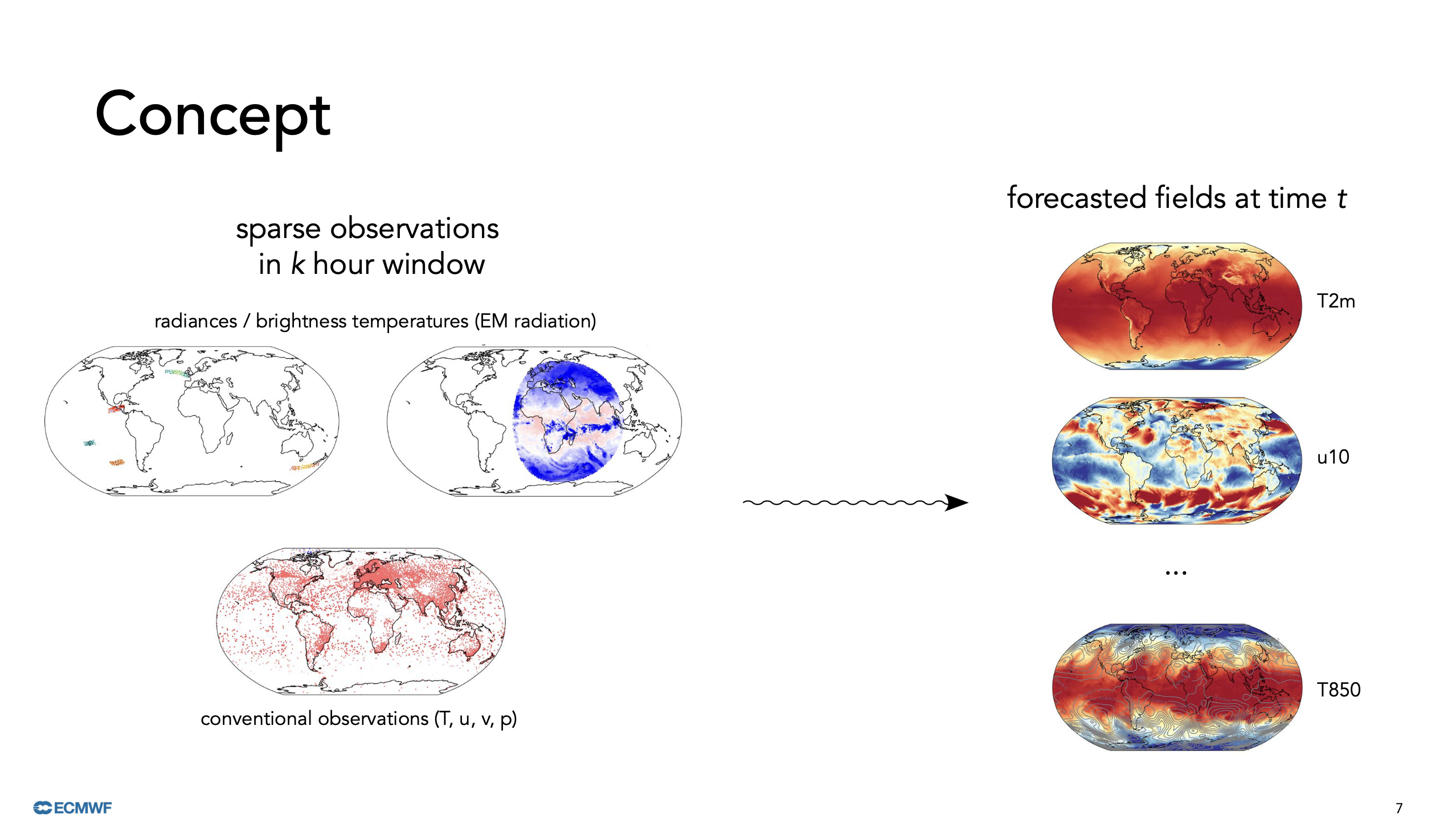

Current data-driven models for weather prediction are typically trained on analyses provided by physics-based data assimilation (DA) systems. These systems create regular grids of key variables such as temperature, pressure, wind speed, and precipitation by interpolating between observations. However, during this process, a significant amount of observational data is discarded due to uncertainties and mismatches, leading to potential loss of valuable information. One central theme of the workshop was how to utilize observations directly in machine learning models. Direct observations refer to raw data collected straight from surface stations, satellites, and radars. The challenge lies in the sparse distribution of these observations, which requires the model to handle arbitrary grids. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have the capability to manage such inputs effectively.

Direct observations can be integrated into machine learning models in three primary ways:

- Enhancing the initial state for a forecast

- Serving as additional input during training

- Acting as the sole input for end-to-end machine learning models

Christian Lessig presented on training and initializing models directly from observations. He suggested using both local and global neural networks for assimilation, and a separate network for forecasting (arXiv:2407.15586). Training these networks involves a sophisticated pre-training procedure: Lessig advocated for masking observations to learn probability distributions between them. This method ensures that the network correctly interpolates between observations in space and time, a concept I find very intriguing. However, I’m skeptical about the necessity of having two separate networks for data assimilation and forecasting. A more elegant solution might be to input the observations directly into the forecasting network without converting the initial state into a regular grid. Of course, when rolling out a forecast, the input will eventually be on a regular grid for subsequent lead times as the network output, but the models don’t need to restrict themselves to a specific input grid.

Anna Vaughan discussed the end-to-end model Aardvark, which follows a typical encoder-decoder architecture. They made a notable observation: the model’s performance improved by 25% when trained on both direct observations and ERA5, as opposed to only on direct observations. Additionally, the model showed similar performance to ECMWF’s HRES forecast, although this comparison was made at a 1.41° spatial resolution. It’s important to highlight that both models mentioned were proof-of-concept rather than fully optimized solutions.

The task of converting sparse observations into comprehensive field predictions is formidable. Slide from Christian Lessig’s presentation (arXiv:2407.15586).

Conclusions

There is no doubt that data-driven models represent the future of weather forecasting. Despite the challenges that arise in developing these models, such as the smoothing problem, viable solutions exist to address these issues. Data-driven models are anticipated to be more versatile than traditional numerical weather prediction models, with the potential to directly incorporate raw observations, as previously discussed.

The technology is now available to develop cutting-edge operational probabilistic models, both regional and global, that feature high spatial and temporal resolution. These models can incorporate direct inputs from a variety of sparse observations, including those from SYNOP stations, satellite radiances, radar, and airplanes. Although the development and testing of these models are time-consuming processes, the current focus on data-driven approaches in weather forecasting suggests that advancements will continue at a rapid pace.

One of the primary responsibilities of meteorological institutes is to issue warnings for extreme weather to safeguard life and property. Therefore, I hope to see an even greater emphasis on extreme weather prediction at the next workshop on large-scale deep learning for the Earth system. I look forward to attending and contributing again next year!

Feel free to drop a comment or question below if you have thoughts or experiences you’d like to share.